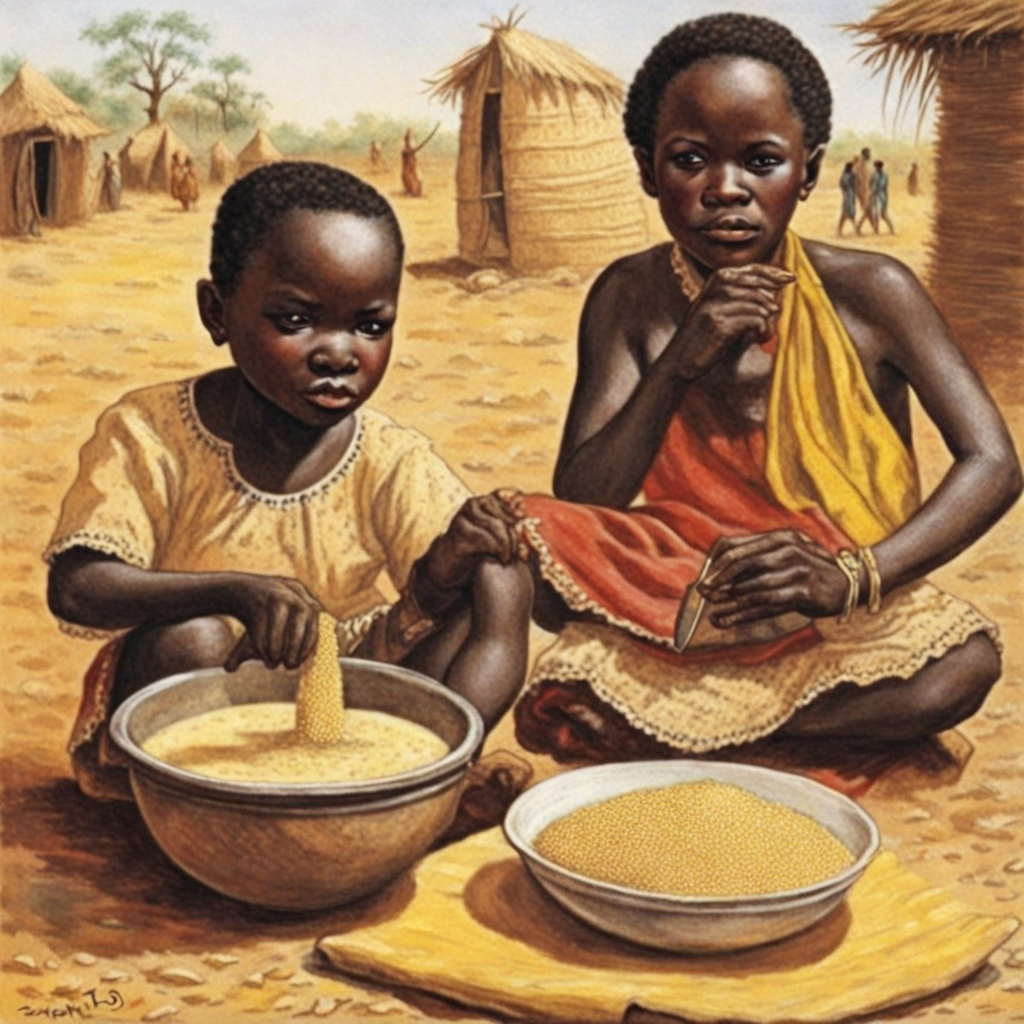

Tô

Tô is a traditional dish from Mali, particularly popular among the Bambara people, and is considered a staple in the West African culinary landscape. The dish is primarily made from millet or sorghum flour, which is known for its nutritional value and ability to sustain energy. Tô serves as a vital source of carbohydrates and is often consumed as a base for various accompaniments, making it an essential part of the Malian diet. Historically, Tô is deeply rooted in the agricultural practices of the region, where millet and sorghum are cultivated extensively. These grains have been a part of the local diet for centuries, reflecting the resilience and resourcefulness of the communities that rely on them. The dish is not only a source of sustenance but also a symbol of cultural identity, often prepared during communal gatherings and celebrations. Over time, Tô has evolved, incorporating various local ingredients and flavors, yet it remains a testament to Mali’s rich culinary heritage. The flavor profile of Tô is subtle and earthy, with a slightly nutty taste that comes from the grains. Its texture is dense and cohesive, resembling a thick porridge or dough-like consistency, which allows it to be molded into balls or served on a plate. While Tô itself is relatively bland, it is designed to complement a wide array of sauces that are rich in spices and flavors, such as peanut sauce, okra stew, or various vegetable sauces. This versatility makes Tô an excellent canvas for showcasing the

How It Became This Dish

Tô: A Culinary Tradition of Mali Origins and Ingredients Tô, a traditional dish from Mali, is a staple food that has deep roots in the cultural and agricultural practices of the Malinke people and other ethnic groups in the region. The dish is primarily made from millet, sorghum, or maize, which are staple grains in West Africa. These grains are ground into flour, which is then mixed with water and cooked to form a thick, dough-like consistency. The process of making tô is labor-intensive; it requires skill and patience to achieve the perfect texture, which is sticky yet firm enough to be molded into a ball. Millet and sorghum have been cultivated in the Sahel region for thousands of years, dating back to ancient agricultural practices that predate the arrival of European colonizers. These grains are well-suited to the arid climate of Mali, making them vital to food security in this region. As a result, tô not only represents a culinary tradition but also symbolizes the resilience of communities that rely on these crops for their sustenance. Cultural Significance Tô is more than just a meal; it is a cultural symbol that embodies the communal spirit of the Malian people. Traditionally, tô is served during communal gatherings and family celebrations, such as weddings, naming ceremonies, and harvest festivals. The dish is often served with a variety of sauces, typically made from groundnut, okra, or leaf-based sauces, adding flavor and nutritional value. In many Malian households, preparing tô is a communal activity. Families often come together to grind the grains, mix the dough, and cook it over an open fire. This process fosters a sense of togetherness and reinforces social bonds within the community. Tô is often eaten with the hands, emphasizing the communal aspect of the meal. Diners typically form small balls of the dish and dip them into the accompanying sauces, creating a tactile and interactive dining experience. The dish is also significant in terms of cultural identity. For the Malinke, the preparation and consumption of tô are often associated with their agrarian lifestyle and the rhythms of the seasons. The dish serves as a reminder of their heritage and the importance of agriculture in their history. Tô has transcended its role as mere sustenance; it is an expression of identity, pride, and continuity within the community. Development Over Time As Mali's political landscape has changed over the centuries, so too has the significance and preparation of tô. The Mali Empire, which flourished between the 13th and 16th centuries, was a major center of trade and culture in West Africa. During this period, the exchange of culinary practices and ingredients flourished, leading to the incorporation of new flavors and techniques into traditional recipes. Although tô remained a staple, the introduction of spices and flavors from trade routes began to influence how it was served and enjoyed. Colonialism in the late 19th and early 20th centuries brought profound changes to Malian society, including shifts in agricultural practices and diet. The introduction of cash crops and the imposition of foreign food systems disrupted traditional foodways. Yet, tô remained a constant in the Malian diet, serving as a source of nourishment during times of hardship. After Mali gained independence in 1960, there was a resurgence of interest in traditional foods as a way to reclaim cultural identity. The government encouraged the promotion of local agricultural production and traditional culinary practices. Tô was re-emphasized as a national dish, celebrated for its nutritional value and cultural significance. In this context, it became a symbol of national pride and resistance against the homogenization of global food culture. In the modern era, tô has adapted to changing lifestyles and urbanization. While it remains a staple in rural areas, urban populations have seen shifts in dietary preferences, leading to a blend of traditional and modern practices. Tô is increasingly found in restaurants and street food stalls, often served alongside contemporary sauces and accompaniments. The dish has also found its way into international cuisine, gaining recognition at food exhibitions and cultural festivals around the world. Tô in Contemporary Mali Today, tô continues to be an integral part of Malian cuisine and culture. It is often consumed as part of daily meals, providing essential carbohydrates and energy for labor-intensive lifestyles. The dish is particularly popular among the youth, who appreciate its versatility and the ability to customize it with various sauces and ingredients. Several initiatives have emerged to promote traditional foods like tô as part of a broader movement for sustainable agriculture and food security. These programs emphasize the importance of local grains and the health benefits of traditional diets, aiming to preserve culinary heritage while addressing contemporary nutritional challenges. Educational programs also seek to teach younger generations about the significance of traditional foods, ensuring that the art of preparing tô is passed down through families. Moreover, tô has become emblematic of Mali's rich culinary diversity and cultural heritage on the global stage. Food festivals and cultural showcases highlight the dish as a representation of Malian identity, drawing attention to the importance of traditional foods in a rapidly globalizing world. Chefs and food enthusiasts are increasingly exploring the flavors and techniques of Malian cuisine, bringing tô and other traditional dishes into the culinary spotlight. Conclusion Tô is a dish that embodies the history, resilience, and cultural richness of Mali. From its origins in ancient agricultural practices to its contemporary adaptations, tô serves as a reminder of the enduring connection between food and identity. As Mali continues to navigate the complexities of modern life, this traditional dish remains a symbol of community, heritage, and pride, illustrating the profound role of culinary traditions in shaping cultural narratives. Whether enjoyed in a bustling market or a quiet family home, tô continues to nourish both body and spirit, linking generations through shared culinary experiences.

You may like

Discover local flavors from Mali